I chose to explore the culture of Haitians who practice Vodou, a religion also known as Voodoo, Vodun, Vodoun, Voudun, and Yoruba Orisha. I have just returned from a vacation in the Caribbean (Punta Cana, Dominican Republic), which shares an island with Haiti. While there, I met a man from Haiti and was reminded of a bizarre experience I had in 1998 when I was ridden by an orisha (loa) during an inner-city Christian church service. Thus, I thought this would make an interesting subject for this assignment. To make things simpler in this essay, I will refer to this group simply as Vodou or Vodoun.

Introducing Vodou and Haitian Culture

Vodou is a Caribbean religion blended from African religions and Catholic Christianity. Long stereotyped by the outside world as “black magic,” Vodoun priests and priestesses are also diviners, healers, and religious leaders, who derive most of their income from healing the sick rather than from attacking targeted victims.

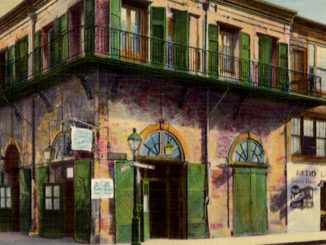

Vodou comes from an African word for “spirit” and can be directly traced to the West African Yoruba people who lived in 18th and 19th century Dahomey. However, its African roots may go back 6,000 years. Today, Vodou is practiced most commonly in the country of Haiti and in the United States around New Orleans, New York, and in Florida. Today over 60 million people practice Vodou throughout the Caribbean and West Indies islands, as well as in North and South America, Africa, and Britain.

During days of slave trade, this religion fused with Catholic Christianity. Therefore, in this current century, children born into rural Haitian families are generally baptized into the Vodou religion as well as in the Catholic church.

Those who practice Vodou believe in a pantheon of gods who control and represent the laws and forces of the universe. In this pantheon, there is a Supreme Deity and the Loa-a large group of lesser deities equivalent to the saints of the Catholic Church. These gods protect people and give special favors through their representatives on earth which are the hougans (priests) and mambos (priestesses).

The Loa (also Lwa or L’wha) are spirits somewhat like saints or angels in Christianity. They are intermediaries between the Creator and humanity. Unlike saints or angels, they are not simply prayed to; they are served. They are each distinct beings with their own personal likes and dislikes, distinct sacred rhythms, songs, dances, ritual symbols, and special modes of service.

Rituals, Behaviors, and Practices Associated with Death and Dying

Haitians who adhere to Vodou do not consider death to be the end of life. They do believe in an afterlife. Followers of Vodoun believe that each person has a soul that has both a gros bon ange (large soul or universal life force), and a ti bon ange (little soul or the individual soul or essence.)

When one dies, the soul essence hovers near the corpse for seven to nine days. During this period, the ti bon ange is vulnerable and can be captured and made into a “spiritual zombie” by a sorcerer. Provided the soul is not captured, the priest or priestess performs a ritual called Nine Night to sever the soul from the body so the soul may live in the dark waters for a year and a day. If this is not done, the ti bon ange may wander the earth and bring misfortune on others.

After a year and a day, relatives of the deceased perform the Rite of Reclamation to raise the deceased person’s soul essence and put it in a clay jar known as a govi. The belief that each person’s life experiences can be passed on to the family or community compels Haitians to implore the spirit of the decease to temporarily possess a family member, priest (houngan), or priestess (mambo) to impart any final words of wisdom.

The clay jar may be placed in the houngan’s or mambo’s temple where the family may come to feed the spirit and treat it like a divine being. At other times, the houngan burns the jar in a ritual called boule zen. This releases the spirit to the land of the dead, where it should properly reside. Another way to elevate the ti-bon-ange is to break the jar and drop the pieces at a crossroad.

The ultimate purpose of death rituals in the Vodoun culture is to send the gros-bon-ange to Ginen, the cosmic community of ancestral spirits, where it will be worshipped by family members as a loa itself. Once the final ritual is done, the spirit is free to abide among the rocks and trees until rebirth. Sixteen incarnations later, spirits merge into the cosmic energy.

Here are some other common behaviors associated with death in the Haitian culture:

· When death is impending, the entire family will gather, pray, cry, and use religious medallions or other spiritual artifacts. Relatives and friends expend considerable effort to be present when death is near.

· Haitians prefer to die at home, but the hospital is also an acceptable choice.

· The moment of death is marked by ritual wailing among family members, friends, and neighbors.

· When a person dies, the oldest family member makes all the arrangements and notifies the family. The body is kept until the entire family can gather.

· The last bath is usually given by a family member.

· Funerals are important social events and involve several days of social interaction, including feasting and the consumption of rum.

· Family members come from far away to sleep at the house, and friends and neighbors congregate in the yard.

· Burial monuments and other mortuary rituals are often costly and elaborate. People are increasingly reluctant to be buried underground. They prefer to be interred above ground in an elaborate multi-chambered tomb that may cost more than the house in which the individual lived while alive.

· Since the body is thought to be necessary for resurrection, organ donation and cremation are not allowed. Autopsy is allowed only if the death occurred as a result of wrong doing or to confirm that the body is actually dead and not a zombie.

Like many Western Christian religions that use a figurative sacrifice to symbolize the consumption of flesh and blood, some Vodoun ceremonies include a literal sacrifice in which chickens, goats, doves, pigeons, and turtles are sacrificed to celebrate births, marriages, and deaths.

Vodou Beliefs about Afterlife

Practitioners of Vodou assume that the souls of all the deceased go to an abode beneath the waters. Concepts of reward and punishment in the afterlife are alien to Vodou.

In Vodou, the soul continues to live on earth and may be used in magic or it may be incarnated in a member of the dead person’s family.

Communion with a god or goddess occurs in the context of possession. The gods sometimes work through a govi, and sometimes take over a living person. This activity is referred to as “mounting a horse” during which the person loses consciousness and the body becomes temporarily possessed by a loa. A special priest (houngan) or priestess (mambo) assists both in summoning the divinities and in helping them to leave at the termination of the possession.

The gros-bon-ange returns to the high solar regions from which its cosmic energy was first drawn; there, it joins the other loa and becomes a loa itself.

Variations

Each group of worshipers is independent and there is no central organization, religious leader, or set of dogmatic beliefs. Rituals and ceremonies vary depending upon family traditions, regional differences, and exposure to the practices of other cultures such as Catholicism, which is the official religion of Haiti.

Some Haitians believe that the dead live in close proximity to the loa, in a place called “Under the Water.” Others hold that the dead have no special place after death.

Burial ceremonies vary according to local tradition and the status of the person. Some families do not express grief aloud until most of the deceased’s possessions have been removed from the home. Persons who are knowledgeable in the funeral customs wash, dress, and place the body in a coffin. Mourners wear white clothing which represents death. A priest may be summoned to conduct the burial service. The burial usually takes place within 24 hours.

Conclusion

Westerners, or so-called logical people, might find Vodoun a strange and exotic mixture of spells, possessions, and rituals. Like any other religion, its purpose is to comfort people by giving them a common bond. Vodoun meshes surprisingly well with Catholicism, the official religion of Haiti. With a supreme being, saint-like spirits, belief in the afterlife and invisible spirits, along with the protection of patron saints, Voodoo isn’t that different from traditional religions.

Proudly WWW.PONIREVO.COM

Source by Yvonne Perry